Funding for Agri-food Data Canada is provided in part by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund

FAIR

In research and data-intensive environments, precision and clarity are critical. Yet one of the most common sources of confusion—often overlooked—is how units of measure are written and interpreted.

Take the unit micromolar, for example. Depending on the source, it might be written as uM, μM, umol/L, μmol/l, or umol-1. Each of these notations attempts to convey the same concentration unit. But when machines—or even humans—process large amounts of data across systems, this inconsistency introduces ambiguity and errors.

The role of standards

To ensure clarity, consistency, and interoperability, standardized units are essential. This is especially true in environments where data is:

-

Shared across labs or institutions

-

Processed by machines or algorithms

-

Reused or aggregated for meta-analysis

-

Integrated into digital infrastructures like knowledge graphs or semantic databases

Standardization ensures that “1 μM” in one dataset is understood exactly the same way in another and this ensures that data is FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable).

UCUM: Unified Code for Units of Measure

One widely adopted system for encoding units is UCUM—the Unified Code for Units of Measure. Developed by the Regenstrief Institute, UCUM is designed to be unambiguous, machine-readable, compact, and internationally applicable.

In UCUM:

-

micromolar becomes

umol/L -

acre becomes

[acr_us] -

milligrams per deciliter becomes

mg/dL

This kind of clarity is vital when integrating data or automating analyses.

UCUM doesn’t include all units

While UCUM covers a broad range of units, it’s not exhaustive. Many disciplines use niche or domain-specific units that UCUM doesn’t yet describe. This can be a problem when strict adherence to UCUM would mean leaving out critical information or forcing awkward approximations. Furthermore, UCUM doesn’t offer and exhaustive list of all possible units, instead the UCUM specification describes rules for creating units. For the Semantic Engine we have adopted and extended existing lists of units to create a list of common units for agri-food which can be used by the Semantic Engine.

Unit framing overlays of the Semantic Engine

To bridge the gap between familiar, domain-specific unit expressions and standardized UCUM representations, the Semantic Engine supports what’s known as a unit framing overlay.

Here’s how it works:

-

Researchers can input units in a familiar format (e.g.,

acreoruM). -

Researchers can add a unit framing overlay which helps them map their units to UCUM codes (e.g.,

"[acr_us]"or"umol/L"). -

The result is data that is human-friendly, machine-readable, and standards-compliant—all at the same time.

This approach offers the both flexibility for researchers and consistency for machines.

Final thoughts

Standardized units aren’t just a technical detail—they’re a cornerstone of data reliability, semantic precision, and interoperability. Adopting standards like UCUM helps ensure that your data can be trusted, reused, and integrated with confidence.

By adopting unit framing overlays with UCUM, ADC enables data documentation that meet both the practical needs of researchers and the technical requirements of modern data infrastructure.

Written by Carly Huitema

Data schemas

Schemas are a type of metadata that provide context to your data, making it more FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable).

At their core, schemas describe your data, giving data better context. There are several ways to create a schema, ranging from simple to more complex. The simplest approach is to document what each column or field in your dataset represents. This can be done alongside your data, such as in a separate sheet within an Excel spreadsheet, or in a standalone text file, often referred to as a README or data dictionary.

However, schemas written as freeform text for human readers have limitations: they are not standardized and cannot be interpreted by machines. Machine-readable data descriptions offer significant advantages. Consider the difference between searching a library using paper card catalogs versus using a searchable digital database—machine-readable data descriptions bring similar improvements in efficiency and usability.

To enable machine-readability, various schema languages are available, including JSON Schema, JSON-LD, XML Schema, LinkML, Protobuf, RDF, and OCA. Each has unique strengths and use cases, but all allow users to describe their data in a standardized, machine-readable format. Once data is in such a format, it becomes much easier to convert between different schema types, enhancing its interoperability and utility.

Overlays Capture Architecture

The schema language Overlays Capture Architecture or OCA has two unique features which is why it is being used by the Semantic Engine.

- OCA embeds digests (specifically, OCA uses SAIDs)

- OCA is organized by features

Together these contribute to what makes OCA a unique and valuable way to document schemas.

OCA embeds digests

OCA uses digests which are digital fingerprints which can be used to unambiguously identify a schema. As digests are calculated directly from the content they identify this means that if you change the original content, the identifier (digest) also changes. Having a digital fingerprint calculated from the content is important for research reproducibility – it means you can find a digital object and if you have the identifier (digest) you can verify if the content has been changed. We have written a blog post about how digests are calculated and used in OCA.

OCA is organized by features

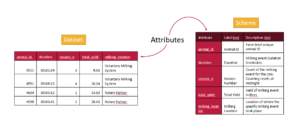

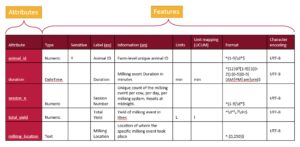

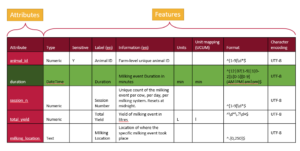

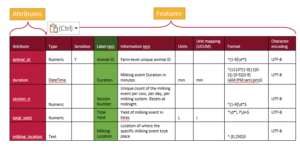

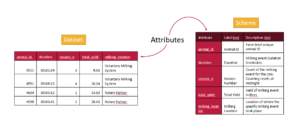

A schema describes the attributes of a dataset (typically the column headers) for a variety of features. A schema can be very simple and use very few features to describe attributes, but a more detailed schema will describe many features of each attribute.

We can represent a schema as a table, with rows for each attribute and a column for each feature.

A tabular representation of a schema provides a clear overview of all the attributes and features used to describe a dataset. While schemas may be visualized as tables, they are ultimately saved and stored as text documents. The next step is to translate this tabular information into a structured text format that computers can understand.

From the table, there are two primary approaches to organizing the information in a text document. One method is to write it row by row, documenting an attribute followed by the values for each of its features. This approach, often called attribute-by-attribute documentation, is widely used in schema design such as JSON Schema and LinkML.

Schemas can also be written column by column, focusing on features instead of attributes. In this feature-by-feature approach (following the table in the figure above), you start by writing out all the data types for each attribute, then specify what is sensitive for each attribute, followed by providing labels, descriptions, and other metadata. These individual features, referred to as overlays in this schema architecture, offer a modular and flexible way to organize schema information. The Overlays Capture Architecture (OCA) is a global open overlay schema language that uses this method, enabling enhanced flexibility and modularity in schema design.

What is important for OCA is each overlay (feature) are given digests (the SAIDs). Each of the columns above is written out and a digest calculated and assigned, one digest for each feature. Then all the parts are put together and the entire schema is given a digest. In this way, all the content of a schema is bound together and it is never ambiguous about what is contained in a schema.

Why schema organization matters

Why does it matter whether schemas are written attribute-by-attribute or feature-by-feature? While we’ll explore this in greater detail in a future blog post, the distinction plays a critical role in calculating digests and managing governance in decentralized ecosystems.

A digest is a unique identifier for a piece of information, allowing it to be governed in a decentralized environment. When ecosystems of researchers and organizations agree on a specific digest (e.g., “version one schema” of an organization with digest xxx), they can agree on the schema’s validity and use.

A feature-by-feature schema architecture is particularly well-suited for governance. It offers flexibility by enabling individual features to be swapped, added, or edited without altering the core content of the data structure. Since the content remains unchanged, the digest also stays the same. This approach not only improves the schema’s adaptability but also enhances both the data’s and the schema’s FAIRness. This modularity ensures that schemas remain effective tools for collaboration and management in dynamic, decentralized ecosystems.

The Semantic Engine

All these details of an OCA schema are taken care of by the Semantic Engine. The Semantic Engine presents a user interface for generating a schema and writes the schema out in the language of OCA; feature by feature. The Semantic Engine calculates all the digests and puts them inside the schema document. It calculates the entire schema digest and it publishes that information when you export the schema. You can view all the digests (SAIDs) calculated for the schema in the readme.txt file.

Written by Carly Huitema

When you’re building a data schema you’re making decisions not only about what data to collect, but also how it should be structured. One of the most useful tools you have is format restrictions.

What Are Format Entries?

A format entry in a schema defines a specific pattern or structure that a piece of data must follow. For example:

- A date must look like YYYY-MM-DD or be in the ISO duration format.

- An email address must have the format name@example.com

- A DNA sequence might only include the letters A, T, G, and C

These formats are usually enforced using rules like regular expressions (regex) or standardized format types.

Why Would You Want to Restrict Format?

Restricting the format of data entries is about ensuring data quality, consistency, and usability. Here’s why it’s important:

✅ To Avoid Errors Early

If someone enters a date as “15/03/25” instead of “2025-03-15”, you might not know whether that’s March 15 or March 25 and what year? A clear format prevents confusion and catches errors before they become a problem.

✅ To Make Data Machine-Readable

Computers need consistency. A standardized format means data can be processed, compared, or validated automatically. For example, if every date follows the YYYY-MM-DD format, it’s easy to sort them chronologically or filter them by year. This is especially helpful for sorting files in folders on your computer.

✅ To Improve Interoperability

When data is shared across systems or platforms, shared formats ensure everyone understands it the same way. This is especially important in collaborative research.

Format in the Semantic Engine

Using the Semantic Engine you can add a format feature to your schema and describe what format you want the data to be entered in. While the schema writes the format rule in RegEx, you don’t need to learn how to do this. Instead, the Semantic Engine uses a set of prepared RegEx rules that users can select from. These are documented in the format GitHub repository where new format rules can be proposed by the community.

After you have created format rules in your schema you can use the Data Entry Web tool of the Semantic Engine to verify your results against your rules.

Final Thoughts

Format restrictions may seem technical, but they’re essential to building reliable, reusable, and clean data. When you use them thoughtfully, they help everyone—from data collectors to analysts—work more confidently and efficiently.

Written by Carly Huitema

In previous blog posts, we’ve discussed identifiers—specifically, derived identifiers, which are calculated directly from the digital content they represent. The key advantage of a derived identifier is that anyone can verify that the cited content is exactly what was intended. When you use a derived identifier, it ensures that the digital resource is authentic, no matter where it appears.

In contrast, authoritative identifiers work differently. They must be resolved through a trusted service, and you have to rely on that service to ensure the identifier hasn’t been altered and that the target hasn’t changed.

The Limitations of Derived Identifiers

One drawback of derived identifiers is that they only work for content that can be processed to generate a unique digest. Additionally, once an identifier is created, the content can no longer be updated. This can be a challenge when dealing with dynamic content, such as an evolving dataset or a standard that goes through multiple versions.

This brings us to the concept of identity, which goes beyond a simple identifier.

What Does Identity Mean?

Let’s take an example. The Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (GA4GH) publishes a data standard called Phenopackets. In this case Phenopackets is an identifier. Currently, there are two released versions (and two identifiers). However, anyone could create a new schema and call it “Phenopackets v3.” The key question is: is just naming something and giving it an identifier enough to have it be recognized as Phenopackets v3?

A name is not enough, what also matters is whether GA4GH itself releases “Phenopackets v3.” The identifier alone isn’t enough—we care about who endorses it. In this case, identity comes from GA4GH, the governing organization of Phenopackets.

Identity Through Reputation

Identity is established through reputation which is gained in two main ways:

- Transferred reputation – When an official organization (like GA4GH) endorses an identifier, the identity is backed by its authority and reputation.

- Acquired reputation – Even without a governing body, something gains identity via reputation if it becomes widely recognized and trusted.

For example, Bitcoin was created by an anonymous person (or group) using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto—a name that doesn’t link to any legal identity which could grant it some reputation. Yet, the name Satoshi Nakamoto has strong identity via acquired reputation because of Bitcoin’s success and widespread recognition.

The key is that identity isn’t just about an identifier—it’s about who assigns it and why people trust it. To fully capture identity, we need to track not only the identifier but also the authority or reputation behind it.

How Do We Use an Identity?

Right now, we don’t have a universal system for identifying and verifying identity in a structured, machine-readable way. This is because identity is a combination of both an identifier and associated reputation/authority behind the identity and our current systems for identifiers don’t clearly recognize these two aspects of identity. Instead, we rely on indirect methods, like website URLs and domain names, to be a stand-in for the identity authority.

For example, if you want to verify the Phenopackets schema’s identity you would want to search out its associated authority. You might search for the Phenopackets name (the identifier) online or follow a link to its official GitHub repository. But how do you know that the GitHub page is legitimate? To confirm, you would check if the official GA4GH website links to it. Otherwise, anyone could create a GitHub repository and name it Phenopackets. The identifier is not enough, you also need to find the authority associated with the identity.

Another example of how we present the authority behind an identity are the academic journals. When they publish research, they add their reputation and peer-review process to build the reputation and identity of a paper. However, this system has flaws. When researchers cite papers they use DOIs which are specific identifiers of the journal article. The connection between the publication’s DOI to the identity of the paper is not standardized which makes discovery of important changes to the paper such as corrections and retractions challenging. Sometimes when you find the article on the journal webpage you might also find the retraction notice but this doesn’t always happen. This disconnect between identifiers and identity of publications leads to the proliferation of zombie publications which continue to be used even after they have been debunked.

Future Directions

As it stands, we lack effective tools for managing digital identity. This gap creates risks, including identity impersonation and difficulties in tracking updates, corrections, or retractions. Because our current citation system focuses on identifiers without strong linksing them to identity, important information can get lost. Efforts are underway to address these challenges, but we’re still in the early stages of finding solutions.

One early technology to address the growth of an identity has been Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs). We’ll talk more about them later, but they allow an identifier to be assigned to an identity that evolves and is provably under the control of an associated governance authority.

We hope this post has helped clarify the distinction between identifiers and identity which are often entangled — and why finding better ways to assign and verify identity is a problem worth solving.

Written by Carly Huitema

I left off my last blog post with a question – well, actually a few questions: WHO owns this data? The supervisor – who is the PI on the research project you’ve been hired onto? OR you as the data collector and analyser? Hmmm…… When you think about these questions – the next question becomes WHO is responsible for the data and what happens to it?

As you already know there really are NO clear answers to these questions. My recommendation is that the supervisor, PI, lab manager, sets out a Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) guide for data collection. Yes, I know this really does NOT address the data ownership question – but it does address my last question: WHO is responsible for the data and what happens to it? And let’s face it – isn’t that just another elephant in the room? Who is responsible for making the research data FAIR?

Oh my, have I just jumped into another rabbit hole?

We have been talking about FAIR data, building tools, and making them accessible to our research community and beyond – BUT? are we missing the bigger vision here? I talk to researchers and most agree that they want to make their data FAIR and share it beyond their lab – BUT…. let’s be honest – that’s a lot of work! Who is going to do it? Here, at ADC, our goal is to work with our research community to help them make agri-food data (and beyond) FAIR – and we’ve been creating tools, creating training materials, and now we are on the precipice of changing the research data culture – well I thought we were – and now I’m left wondering – who is RESPONSIBLE for setting out these procedures in a research project? WHO should be the TRUE force behind changing the data culture and encouraging FAIR research data?

Don’t worry – for anyone reading this – we are VERY set and determined to changing the research data culture by continuing to make the transition to FAIR data – easy and straightforward. It’s just an interesting question and one I would love for you all to consider – WHO is RESPONSIBLE for the data collected in a research project?

Till the next post – let’s consider Copyright and data – oh yes! Let’s tackle that hurdle 🙂

![]()

image created by AI

As data archivists and data analysts, this question crops up a lot! Let’s be honest with ourselves there is NO one answer fits all here! I would love to say YES we should share our data – but then I step back and say HOLD IT! I don’t want anyone being able to access my personal information – so maybe… we shouldn’t share our data. But then the reasonable part of me goes WHOA! What about all that research data? My BSc, MSc, PhD data – that should definitely be shared. But.. should it really? Oh… I can go back and forth all day and provide you with the whys to share data and the why nots to share data. Hmmm…

So, why am I bringing this up now (and again) and in this forum? Conversations I’ve been having with different data creators – that’s it. But why? Because everyone has a different reason why or why not to share their data. So I want us all to take a step back and remember that little acronym FAIR!

I’m finding that more and more of our community recognizes FAIR and what it stands for – but does everyone really remember what the FAIR principles represent? There seems to be this notion that if you have FAIR data it means you are automatically going to share it. I will say NOPE that is not true!!! So if we go back and read the FAIR principles a little closer – you can see that they are referring to the (meta)data!!

Let’s dig into that just a little bit…… Be honest – is there anything secret about the variables you are collecting? Remember we are not talking about the actual data – just the description of what you are collecting. I will argue that about 98% of us are able to share the metadata or description of our datasets. For instance, I am collecting First Name of all respondents, but this is sensitive information. Fabulous!! I now know you are collecting first names and it’s sensitive info, which means it will NOT be shared! That’s great – I know that data will not be shared but I know you have collected it! The data is FAIR! I’ll bet you can work through this for all your variables.

Again – why am I talking about this yet again? Remember our Semantic Engine? What does it do? Helps you create the schema to your dataset! Helps you create or describe your dataset – making it FAIR! We can share our data schemas – we can let others see what we are collecting and really open the doors to potential and future collaborations – with NO data sharing!

So what’s stopping you? Create a data schema – let it get out – and share your metadata!

![]()

image created by AI

Broken links are a common frustration when navigating the web. If you’ve ever clicked on a reference only to land on a “404 Not Found” page, you know how difficult it can be to track down missing content. In research, broken links pose a serious challenge to reproducibility—if critical datasets, software, or methodologies referenced in a study disappear, how can others verify or build upon the original work?

Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) help solve this problem by creating stable, globally unique references to digital and physical objects. Unlike regular URLs, PIDs are designed to persist beyond the lifespan of URL links to a webpage or database, ensuring long-term access to research outputs.

Persistent Identifiers should be used to uniquely (globally) identify a resource, they should persist, and it is very useful if you can resolve them so when you put in the identifier (somewhere) you get taken to the thing it references. Perhaps the most successful PID in research is the DOI – the Digital Object Identifier which is used to provide persistent links to published digital objects such as papers and datasets. Other PIDs include ORCiDs, RORs and many others existing or being proposed.

We can break identifiers into two basic groups – identifiers created by assignment, and identifiers that are derived. Once we have the identifier we have options on how they can be resolved.

Identifiers by assignment

Most research identifiers in use are assigned by the governing body. An identifier is minted (created) for the object they are identifying and is added to a metadata record containing additional information describing the identified object. For example, researchers can be identified with an ORCiD identifier which are randomly generated 16 digit numbers. Metadata associated with the ORCiD value includes the name of the individual it references as well as information such as their affiliations and publications.

We expect that the governance body in charge of any identifier ensures that they are globally unique and that they can maintain these identifiers and associated metadata for years to come. If an adversary (or someone by mistake) altered the metadata of an identifier they could change the meaning of the identifier by changing what resource it references. My DOI associated with my significant research publication could be changed to referencing a picture of a chihuahua.

Other identifiers such as DOIs, PURLs, ARKs and RORs are also generated by assignment and connected to the content they are identifying. The important detail about identifiers by assignment is that if you find something (person, or organism or anything else) you cannot determine which identifier it has been assigned unless you can match it to the metadata of an existing identifier. These assigned identifiers aren’t resilient, they depend on the maintenance of the identifier documentation. If the organization(s) operating these identifiers goes away, so does the identifier. All research that used these identifiers for identifying specific objects has the research equivalent of the web’s broken link.

We also have organizations that create and assign identifiers for physical objects. For example, the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) mints identifiers, maintains metadata and stores the canonical, physical cell lines and microorganism cultures. If the samples are lost or if ATCC can no longer maintain the metadata of the identifiers then the identifiers lose their connection. Yes, there will be E. coli DH5α cells everywhere around the world, but cell lines drift, and microorganisms growing in labs mutate which was the challenge the ATCC was created to address.

To help record which identifier has been assigned to a digital object you could include the identifier inside the object, and indeed this is done for convenience. Published journal articles will often include the DOI in the footer of the document, but this is not authoritative. Anyway could publish a document and add a fake DOI, it is only the metadata as maintained by the DOI organization that can be considered authentic and authoritative.

Identifiers by derivation

Derived identifiers are those where the content of the identifier is derived from the object itself. In chemistry for example, the IUPAC naming convention provides several naming conventions to systematically identify chemical compounds. While (6E,13E)-18-bromo-12-butyl-11-chloro-4,8-diethyl-5-hydroxy-15-methoxytricosa-6,13-dien-19-yne-3,9-dione does not roll off the tongue, anyone given the chemical structure would derive the same identifier. Digital objects can use an analogous method to calculate identifiers. There exist hashing functions which can reproducibly generate the same identifier (digest) for a given digital input. The md5 checksums sometimes associated with data for download is an example of a digest produced from a hashing function.

An IUPAC name is bi-directional, if you are given the structure you can determine the identifier and vice-versa. A digest is a one-way function – from an identifier you can’t go back and calculate the original content. This one-way feature makes digests useful for identifying sensitive objects such as personal health datasets.

With derived identifiers you have globally unique and secure identifiers which persist indefinitely but this still depends on the authority and authenticity of the method for deriving the identifiers. IUPAC naming rules are authoritative when you can verify the rules to follow come directly from IUPAC (e.g. someone didn’t add their own rules to the set and claim they are IUPAC rules). Hashing functions are also calculated according to a specific function which are typically published widely in the scientific literature, by standards bodies, in public code repositories and in function libraries. An important point about derived identifiers is that you can always verify for yourself by comparing the claimed identifier against the derived value. You can never verify an assigned identifier. The authoritative table maintained by the identifiers governance body is the only source of truth.

The Semantic Engine generates schemas where each component of the schema are given derived identifiers. These identifiers are inserted directly into the content of the schema (as self-addressing identifiers) where they can be verified. The schema is thus a self-addressing document (SAD) which contains the SAID.

Resolving identifiers

Once you have the identifier, how do you go from identifier to object? How do you resolve the identifier? At a basic level, many of these identifiers require some kind of look-up table. In this table will be the identifier and the corresponding link that points to the object the identifier is referencing. There may be additional metadata in this table (like DOI records which also contain catalogue information about the digital object being referenced), but ultimately there is a look-up table where you can go from identifier to the object. Maintaining the look-up table, and maintaining trust in the look-up table is a key function of any governance body maintaining an identifier.

For traditional digital identifiers, the content of the identifier look-up table is either curated and controlled by the governance body (or bodies) of the identifier (e.g. DOI, PURL, ARK), or the content may be contributed by the community or individual (ORCiD, ROR). But in all cases we must depend on the governance body of the identifier to maintain their look-up tables. If something happens and the look-up table is deleted or lost we couldn’t recreate it easily (imagine going through all the journal articles to find the printed DOI to insert back into the look-up table). If an adversary (or someone by mistake) altered the look-up table of an identifier they could change the meaning of the identifier by changing what resource it points to. The only way to correct this or identify it is to depend on the systems the identifier governance body has in place to find mistakes, undo changes and reset the identifier.

Having trust in a governance authority to maintain the integrity of the look-up table is efficient but requires complete trust in the governance authority. It is also brittle in that if the organization cannot maintain the look-up table the identifiers lose resolution. The original idea of blockchain was to address the challenge of trust and resilience in data management. The goal was to maintain data (the look-up table) in a way that all parties could access and verify its contents, with a transparent record of who made changes and when. Instead of relying on a central server controlled by a governance body (which had complete and total responsibility over the content of the look-up table), blockchain distributes copies of the look-up table to all members. It operates under predefined rules for making changes, coupled with mechanisms that make it extremely difficult to retroactively alter the record.

Over time, various blockchain models have emerged, ranging from fully public systems, such as Bitcoin’s energy-intensive Proof of Work approach, to more efficient Proof of Stake systems, as well as private and hybrid public-private blockchains designed for specific use cases. Each variation aims to balance transparency, security, efficiency, and accessibility depending on the application. Many of the Decentralized Identity (the w3c standard DID method) identifiers use blockchains to distribute their look-up tables to ensure resiliency and to have greater trust when many eyes can observe changes to the look-up table (and updates to the look-up table are cryptographically controlled). Currently there are no research identifiers that use any DID method or blockchain to ensure provenance and resiliency of identifiers.

With assigned identifiers only the organization that created the identifier can be the authoritative source of the look-up table. Only the organization holds the authoritative information linking the content to the identifier. For derived identifiers the situation is different. Anyone can create a look-up table to point to the digital resource because anyone can verify the content by recalculating the identifier and comparing it to the expected value. In fact, digital resources can be copied and stored in multiple locations and there can be multiple look-up tables pointing to the same object copied in a number of locations. As long as the identifiers are the same as the calculated value they are all authoritative. This can be especially valuable as organizational funding rises and falls and organizations may lose the ability to maintain look-up tables and metadata directories.

Summary

Persistent identifiers (PIDs) play a crucial role in ensuring the longevity and accessibility of research outputs by providing stable, globally unique references to digital and physical objects. Unlike traditional web links, which can break over time, PIDs persist through governance and resolution mechanisms. There are two primary types of identifiers: those assigned by an authority (e.g., DOIs, ORCiDs, and RORs) and those derived from an object’s content (e.g., IUPAC chemical names and cryptographic hashes). Assigned identifiers depend on a central governance body to maintain their authenticity, whereas derived identifiers allow independent verification by recalculating the identifier. Regardless of their method of generation, both types of identifiers benefit from resolution services which can either be centralized or decentralized. As research infrastructure evolves, balancing governance, resilience, and accessibility in identifier systems remains a key concern for ensuring long-term reproducibility and trust in scientific data.

Written by Carly Huitema

Digests as identifiers

Overlays Capture Architecture (OCA) uses a type of digest called SAIDs (Self-Addressing IDentifiers) as identifiers. Digests are essentially digital fingerprints which provide an unambiguous way to identify a schema. Digests are calculated directly from the schema’s content, meaning any change to the content results in a new digest. This feature is crucial for research reproducibility, as it allows you to locate a digital object and verify its integrity by checking if its content has been altered. Digests ensure trust and consistency, enabling accurate tracking of changes. For a deeper dive into how digests are calculated and their role in OCA, we’ve written a detailed blog post exploring digest use in OCA.

Digests are not limited to schemas, digests can be calculated and used as an identifier for any type of digital research object. While Agri-food Data Canada (ADC) is using digests initially for schemas generated by the Semantic Engine (written in OCA), we envision digests to be used in a variety of contexts, especially for the future identification of research datasets. This recent data challenge illustrates the current problem with tracing data pedigree. If research papers were published with digests of the research data used for the analysis the scholarly record could be better preserved. Even data held in private accounts could be verified that they contain the data as it was originally used in the research study.

Decentralized research

The research ecosystem is in general a decentralized ecosystem. Different participants and organizations come together to form nodes of centralization for collaboration (e.g. multiple journals can be searched by a central index such as PubMed), but in general there is no central authority that controls membership and outputs in a similar way that a government or company might. Read our blog post for a deeper dive into decentralization.

Centralized identifiers such as DOI (Digital Object Identifier) are coordinated by a centrally controlled entity and uniqueness of each identifier depends on the centralized governance authority (the DOI Foundation) ensuring that they do not hand out the same DOI to two different research papers. In contrast, digests such as SAIDs are decentralized identifiers. Digests are a special type of identifier in that no organization handles their assignment. Digests are calculated from the content and thus require no assignment from any authority. Calculated digests are also expected to be globally unique as the chance of calculating the same SAID from two different documents is vanishingly small.

Digests for decentralization

The introduction of SAIDs enhances the level of decentralization within the research community, particularly when datasets undergo multiple transformations as they move through the data ecosystem. For instance, data may be collected by various organizations, merged into a single dataset by another entity, cleaned by an individual, and ultimately analyzed by someone else to answer a specific research question. Tracking the dataset’s journey—where it has been and who has made changes—can be incredibly challenging in such a decentralized process.

By documenting each transformation and calculating a SAID to uniquely identify the dataset before and after each change, we have a tool that helps us gain greater confidence in understanding what data was collected, by whom, and how it was modified. This ensures a transparent record of the dataset’s pedigree.

In addition, using SAIDs allows for the assignment of digital rights to specific dataset instances. For example, a specific dataset (identified and verified with a SAID) could be licensed explicitly for training a particular AI model. As AI continues to expand, tracking the provenance and lineage of research data and other digital assets becomes increasingly critical. Digests serve as precise identifiers within an ecosystem, enabling governance of each dataset component without relying on a centralized authority.

Traditionally, a central authority has been responsible for maintaining records—verifying who accessed data, tracking changes, and ensuring the accuracy of these records for the foreseeable future. However, with digests and digital signatures, data provenance can be established and verified independently of any single authority. This decentralized approach allows provenance information to move seamlessly with the data as it passes between participants in the ecosystem, offering greater flexibility and opportunities for data sharing without being constrained by centralized infrastructure.

Conclusion

Self-Addressing Identifiers such as those used in Overlays Capture Architecture (OCA), provide unambiguous, content-derived identifiers for tracking and governing digital research objects. These identifiers ensure data integrity, reproducibility, and transparency, enabling decentralized management of schemas, datasets, and any other digital research object.

Self-Addressing Identifiers further enhance decentralization by allowing data to move seamlessly across participants while preserving its provenance. This is especially critical as AI and complex research ecosystems demand robust tracking of data lineage and usage rights. By reducing reliance on centralized authorities, digests empower more flexible, FAIR, and scalable models for data sharing and governance.

Written by Carly Huitema

Oh WOW! Back in October I talked about possible places to store and search for data schemas. For a quick reminder check out Searching for Data Schemas and Searching for variables within Data Schemas. I think I also stated somewhere or rather sometime, that as we continue to add to the Semantic Engine tools we want to take advantage of processes and resources that already exist – like Borealis, Lunaris, and odesi. In my opinion, by creating data schemas and storing them in these national platforms, we have successfully made our Ontario Agricultural College research data and Research Centre data FAIR.

But, there’s still a little piece to the puzzle that is missing – and that my dear friends is a catalogue. Oh I think I heard my librarian colleagues sigh :). Searching across National platforms is fabulous! It allows users to “stumble” across data that they may not have known existed and this is what we want. But, remember those days when you searched for a book in the library – found the catalogue number – walked up a few flights of stairs or across the room to find the shelf and then your book? Do you remember what else you did when you found that shelf and book? Maybe looked at the titles of the books that were found on the same shelf as the book you sought out? The titles were not the same, they may have contained different words – but the topic was related to the book you wanted. Today, when you perform a search – the results come back with the “word” you searched for. Great! Fabulous! But it doesn’t provide you with the opportunity to browse other related results. How these results are related will depend on how the catalogue was created.

I want to share with you the beginnings of a catalogue or rather catalogues. Now, let’s be clear, when I say catalogue, I am using the following definition: “a complete list of items, typically one in alphabetical or other systematic order.” (from the Oxford English Dictionary). We have started to create 2 catalogues at ADC – one is the Agri-food research centre schema library listing all the data schemas currently available at the Ontario Dairy Research Centre and the Ontario Beef Research Centre and the second is a listing of data schemas being used in a selection of Food from Thought research projects.

As we continue to develop these catalogues, keep an eye out for more study level information and a more complete list of data schemas.

![]()

image created by AI

Understanding Data Requires Context

Data without context is challenging to interpret and utilize effectively. Consider an example: raw numbers or text without additional information can be ambiguous and meaningless. Without context, data fails to convey its full value or purpose.

By providing additional information, we can place data within a specific context, making it more understandable and actionable – more FAIR. This context is often supplied through metadata, which is essentially “data about data.” A schema, for instance, is a form of metadata that helps define the structure and meaning of the data, making it clearer and more usable.

The Role of Schemas in Contextualizing Data

A data schema is a structured form of metadata that provides crucial context to help others understand and work with data. It describes the organization, structure, and attributes of a dataset, allowing data to be more effectively interpreted and utilized.

A well-documented schema serves as a guide to understanding the dataset’s column labels (attributes), their meanings, the data types, and the units of measurement. In essence, a schema outlines the dataset’s structure, making it accessible to users.

For example, each column in a dataset corresponds to an attribute, and a schema specifies the details of that column:

- Units: What units the data is measured in (e.g., meters, seconds).

- Format: What format the data should follow (e.g., date formats).

- Type: Whether the data is numerical, textual, boolean etc.

The more features included in a schema to describe each attribute, the richer the metadata, and the easier it becomes for users to understand and leverage the dataset.

Writing and Using Schemas

When preparing to collect data—or after you’ve already gathered a dataset—you can enhance its usability by creating a schema. Tools like the Semantic Engine can help you write a schema, which can then be downloaded as a separate file. When sharing your dataset, including the schema ensures that others can fully understand and use the data.

Reusing and Extending Schemas

Instead of creating a new schema for every dataset, you can reuse existing schemas to save time and effort. By building upon prior work, you can modify or extend existing schemas—adding attributes or adjusting units to align with your specific dataset requirements.

One Schema for Multiple Datasets

In many cases, one schema can be used to describe a family of related datasets. For instance, if you collect similar data year after year, a single schema can be applied across all those datasets.

Publishing schemas in repositories (e.g., Dataverse) and assigning them unique identifiers (such as DOIs) promotes reusability and consistency. Referencing a shared schema ensures that datasets remain interoperable over time, reducing duplication and enhancing collaboration.

Conclusion

Context is essential to making data understandable and usable. Schemas provide this context by describing the structure and attributes of datasets in a standardized way. By creating, reusing, and extending schemas, we can make data more accessible, interoperable, and valuable for users across various domains.

Written by Carly Huitema