Repositories for Research Data

Generalist and Specialist Data Repositories

Research data repositories can be described along two important dimensions:

-

how broad or specialized their scope is, and

-

where they sit in the research data lifecycle.

Understanding these distinctions helps understand the technologies and repositories available for research data.

Generalist Repositories

Generalist repositories are designed to accept many different kinds of data across disciplines. They prioritize inclusivity and flexibility, offering a common technical platform where researchers can deposit datasets that do not fit neatly into a single domain.

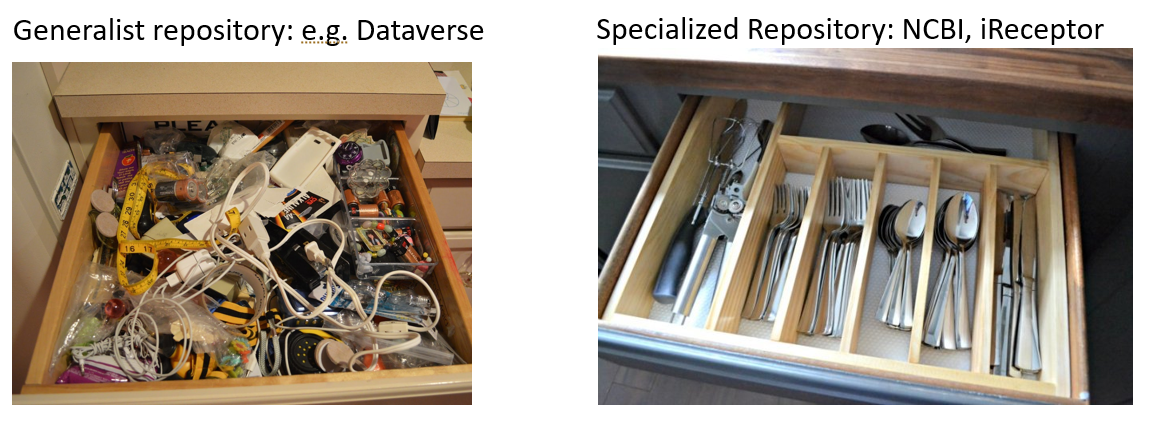

A useful metaphor is the junk drawer in a kitchen. A junk drawer contains many useful items—batteries, spare cables, elastic bands—but finding a specific item often requires some effort. Similarly, generalist repositories can hold valuable datasets, but those datasets may be described with relatively generic metadata and limited domain-specific structure.

As a result, data in generalist repositories can be:

-

Harder to discover through precise searches

-

More difficult to interpret without additional context

-

Less immediately reusable by domain experts

Examples of generalist repositories include Dataverse (Borealis in Canada), Figshare and OSF.

Specialist Repositories

Specialist repositories focus on a specific discipline, data type, or research community. They typically enforce domain-specific metadata standards, controlled vocabularies, and structured submission requirements.

Continuing the kitchen metaphor, specialist repositories resemble a cutlery drawer: clearly organized, purpose-built, and easy to use—provided you are looking for the right type of item. Knives go in one place, forks in another, and everything has a defined role.

Because of this structure, specialist repositories tend to make data:

-

More findable through precise, domain-aware search

-

Easier to interpret due to consistent metadata

-

More interoperable with related tools and systems

-

More reusable for future research

In other words, data in specialist repositories are often more FAIR than data in generalist repositories. However, this specialization also limits what they can accept. Many interdisciplinary datasets—particularly in agri-food research—do not align cleanly with the strict models of existing specialist repositories and therefore end up in generalist ones. Examples of specialist repositories include Genbank, PDB and GEO.

The Research Data Lifecycle: Active and Archival Data

Another important way to think about data repositories is in relation to the research data lifecycle.

Research data typically move through several phases:

-

Planning and collection

-

Processing, active analysis and refinement

-

Publication and dissemination

-

Long-term preservation and reuse

Repositories are often designed to support either active data or archival data, but not both equally well.

Active Data

Active data are produced and used during the course of research. They may be incomplete, frequently updated, or subject to access restrictions due to confidentiality, sensitivity, or competitive concerns.

This is the phase where data are still being cleaned, analyzed, and interpreted. Changes are expected, and collaboration is often ongoing. Most formal repositories are not designed to support this stage, which is typically handled through local storage, shared drives, or project-specific platforms.

Archival Data

Once research is complete and results have been published, data generally move into an archival phase. At this point, datasets are more stable, less likely to change, and often less sensitive—especially if they have been anonymized or if concerns about being “scooped” no longer apply.

Most well-known repositories, including Dataverse, Figshare, and domain-specific archives such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB), are designed primarily for archival data. Their strengths lie in long-term preservation, persistent identifiers (PIDs like DOIs), citation, and access, rather than supporting ongoing analysis or frequent updates.

Bridging the Gaps

It would be inefficient to build a highly specialized repository for every possible type of dataset—much like building a kitchen with a separate drawer for every object that might otherwise end up in the junk drawer. Instead, a more scalable approach is to improve the organization and description of data held in generalist repositories.

Agri-food Data Canada’s approach focuses on developing tools, guidance, and training that help researchers add structure and context to their data wherever it is deposited. By enhancing metadata quality and enabling interoperability between repositories, it becomes possible to make data in generalist repositories more FAIR—without requiring a proliferation of narrowly specialized infrastructure.

Together, specialist and generalist repositories, along with active and archival data systems, form complementary parts of the research data ecosystem. Recognizing their respective roles helps researchers choose appropriate platforms and supports more effective data reuse over time.

Written by Carly Huitema